Filed under: drawing, drawing theory, events, illustration, my antarctica, picturebooks, sketchbook, south africa | Tags: art, books, children's books, creative talks, drawing, illustration, picture books, sketch, south africa, writing, writing seminar

This March 16th I have the immense honour of speaking alongside six truly great children’s book creators in The Writing Barn’s online seminar about nonfiction picture books.

I’ll be speaking on the topic “Making Room for the Illustrator” and touching upon real-world visual research and how illustration can contribute to nonfiction storytelling.

Here is a one-time opportunity to learn new ideas, methods and approaches to creating nonfiction picture books from seven of the most successful book creators in publishing AND help save South Africa’s wildlife at the same time. In this fast and fun, 90 minute event we will cover every facet of the creation process from research and ideas to creating and selling your book. Above all, you will discover how to take known facts and transform them into a true story that is uniquely yours — exactly what agents and editors are searching for.

Led by the amazing group Children’s Book Creators for Conservation, this webinar will be full of unique insights and take aways. This is a charity event with $30 of your registration fee going directly to Wild Tomorrow, a nonprofit working to restore wildlife and wild places in South Africa.

Sign up for the online event here.

Filed under: drawing, drawing theory, illustration, illustrations, sketchbook, writing | Tags: art, children's books, draw daily, drawing, illustration, sketch, sketchbook, sketchbook inspiration, sketching, south africa, travel diary, travel sketchbook, travelogue, watercolour

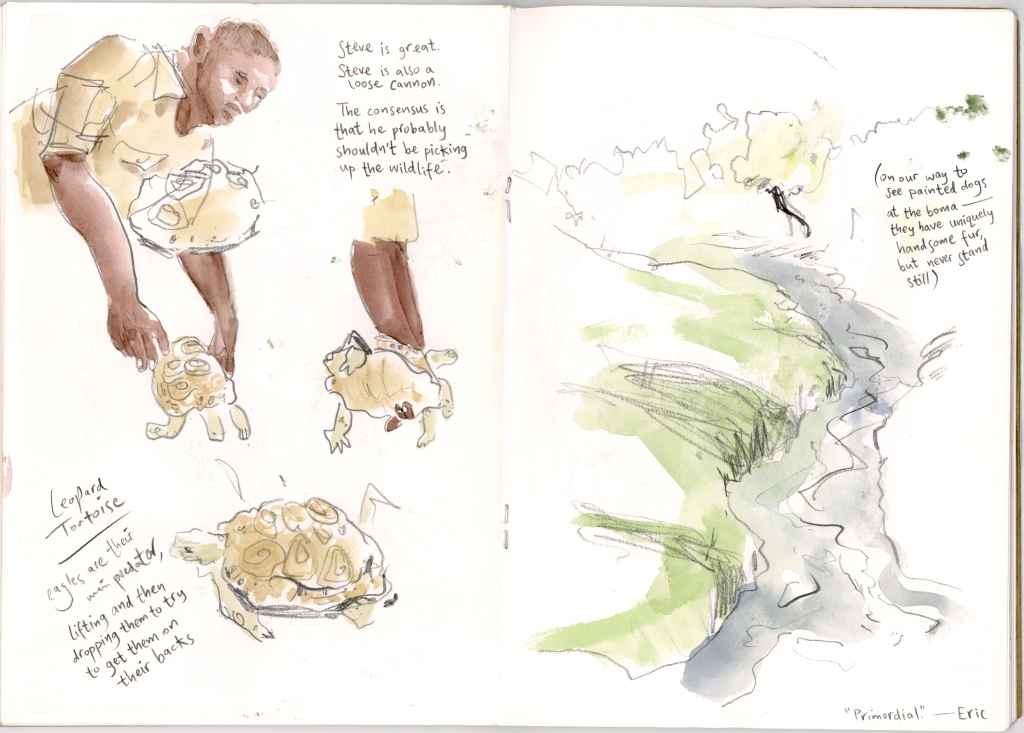

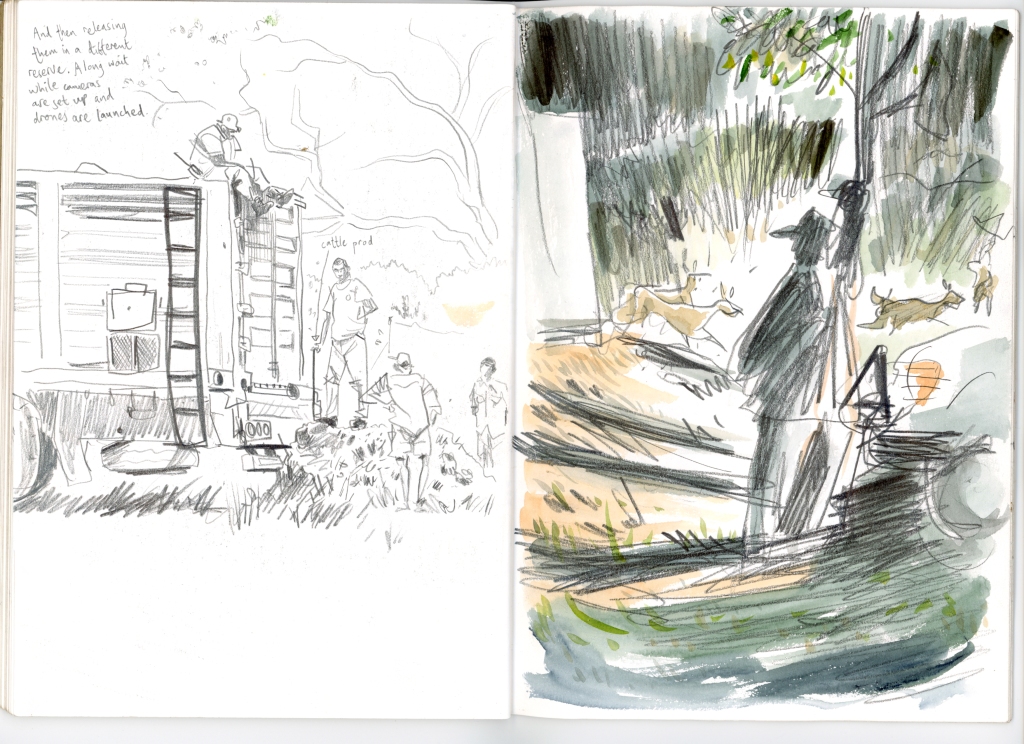

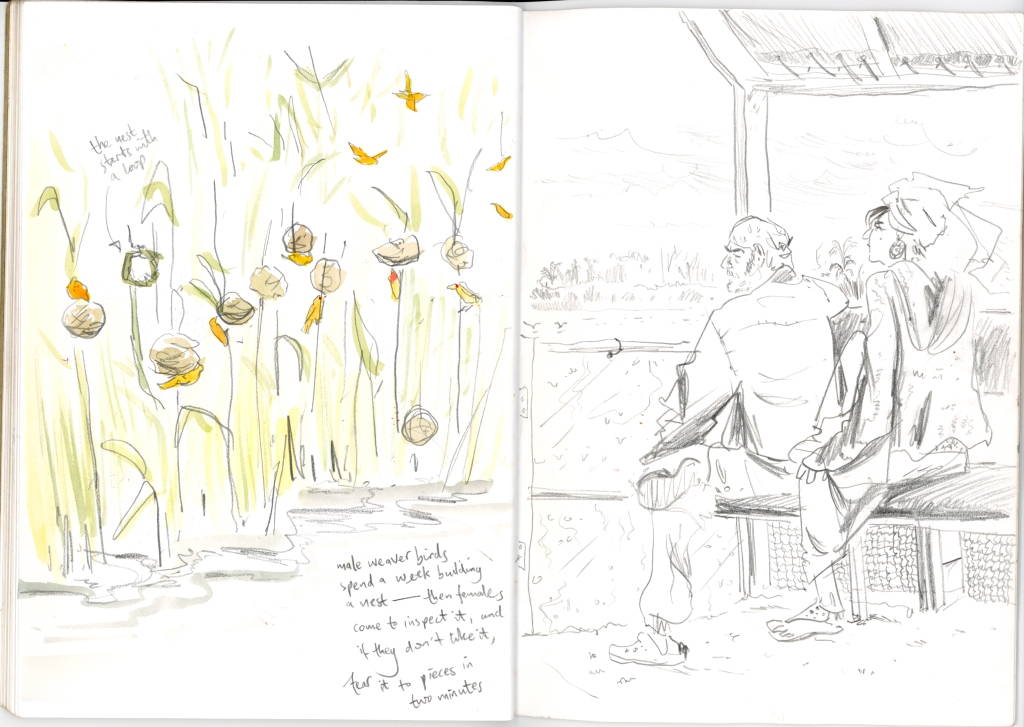

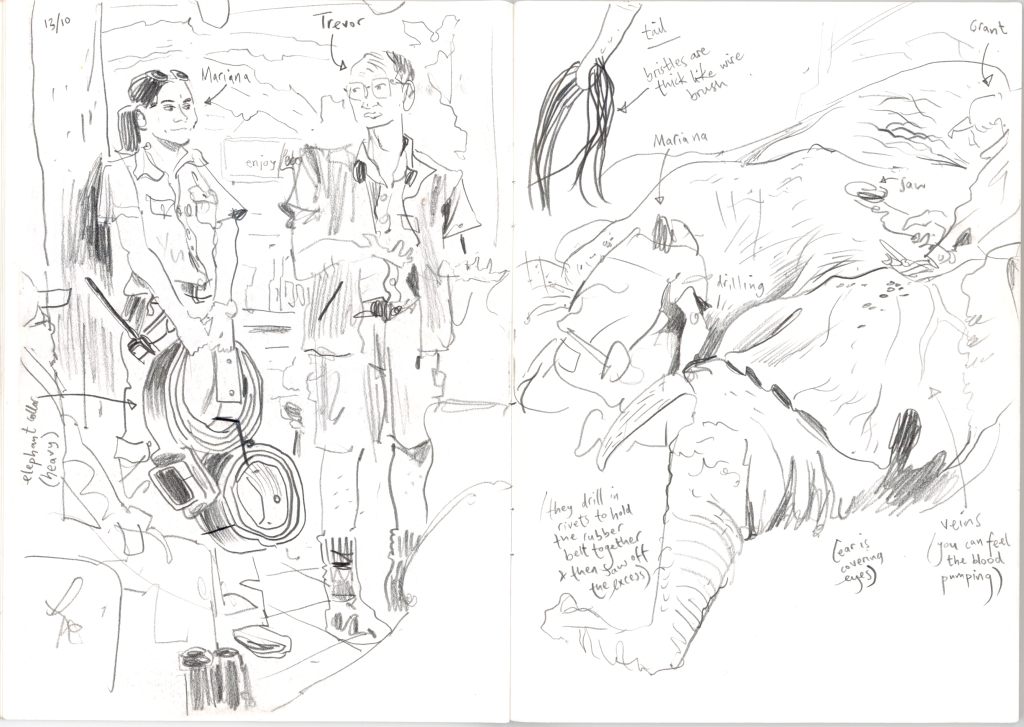

(Cross-post with Wild Tomorrow blog.)

In 2023 I was asked along on a volunteer trip for conservation with Wild Tomorrow. At the time, I hadn’t heard of Wild Tomorrow and I confess: I had no idea what I was signing up for.

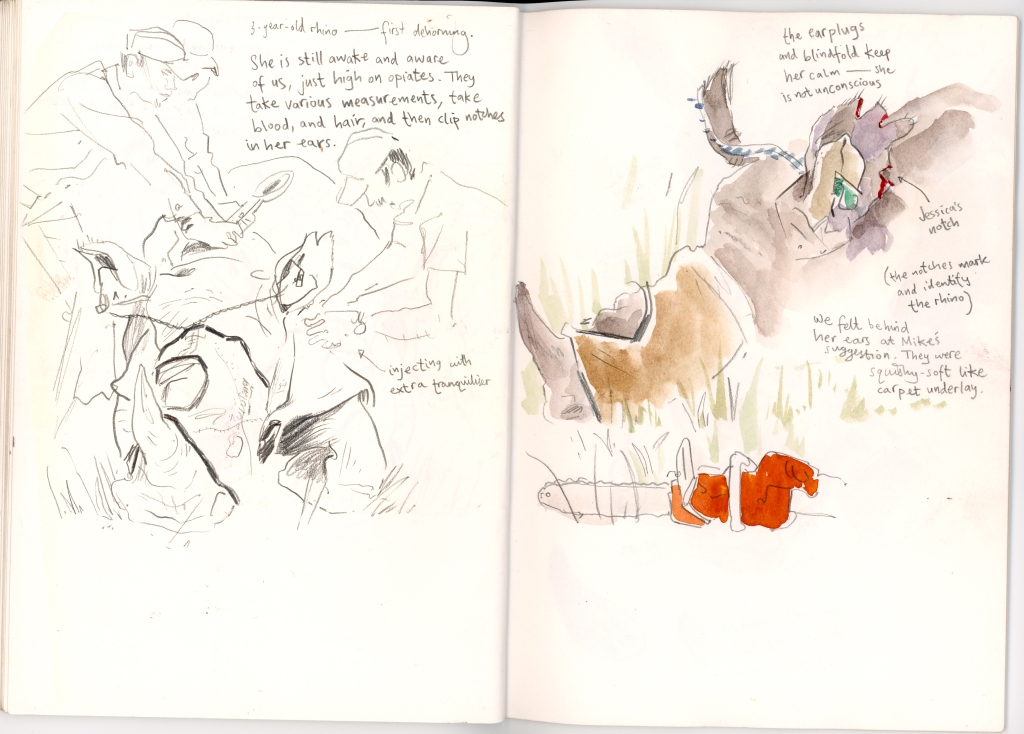

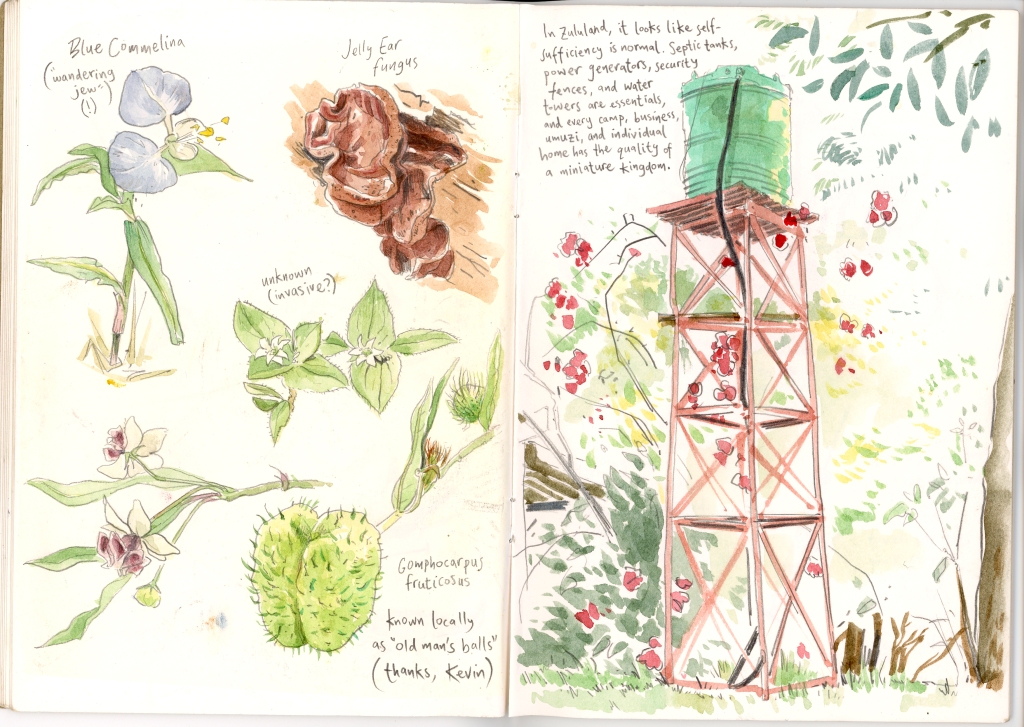

I’m an illustrator and a bit of a writer, and was set to go to the wildlife reserves of KwaZulu-Natal in the east of South Africa for two weeks as part of CBCC (Children’s Books Creators for Conservation, founded just this year by Hayley and John Rocco), ostensibly with the aim of conducting visual research in sketchbooks for a potential book about the subject of wild animal conservation.

Being kind of travel-phobic I approached the trip with some uncertainty. What would these two weeks involve, really? I wasn’t sure. We were provided with an itinerary, which detailed the facts of the unbelievable things we would be doing each day, but these things seemed so far away: what did they really mean?

Sat behind a computer screen in drizzly England, it was hard to think of more than a tourist cliché of ‘go to place, see animals, be amazed.’ And I was worried that I might not be amazed enough, that my heart might not be able to go somewhere so big.

Before this year, I had never had any intention of going to South Africa or seeking out the famous animals of the country, and I’d certainly never been on a trip of this sort. So the opportunity came without preconceptions, and without any notion of what I could contribute, or what I could take from the experience.

This feeling continued even after touching down in Johannesburg and meeting all the lovely, enthused people I would be spending the next two weeks with. ‘Everyone else seems to know what they’re doing here,’ I thought to myself, ‘And I’m not sure that I do.’

But as the days went on, I found myself gradually overwhelmed by the strange new life that Tori and the Wild Tomorrow crew invited us into. In spite of my own hang-ups and misgivings, the country and its people began pulling me into their world, and by the second week, my mind and my heart had been blown wide open, and in time, I began to understand why I was there.

I wasn’t the only one. In conversations with others, I heard similar concerns: being unsure if coming on the trip was a constructive thing, and whether one had something to contribute to the group effort. I guess it’s more natural to have these doubts than I realised. But the doubts we had began to be overtaken by the undeniable optimism of what we were involved with.

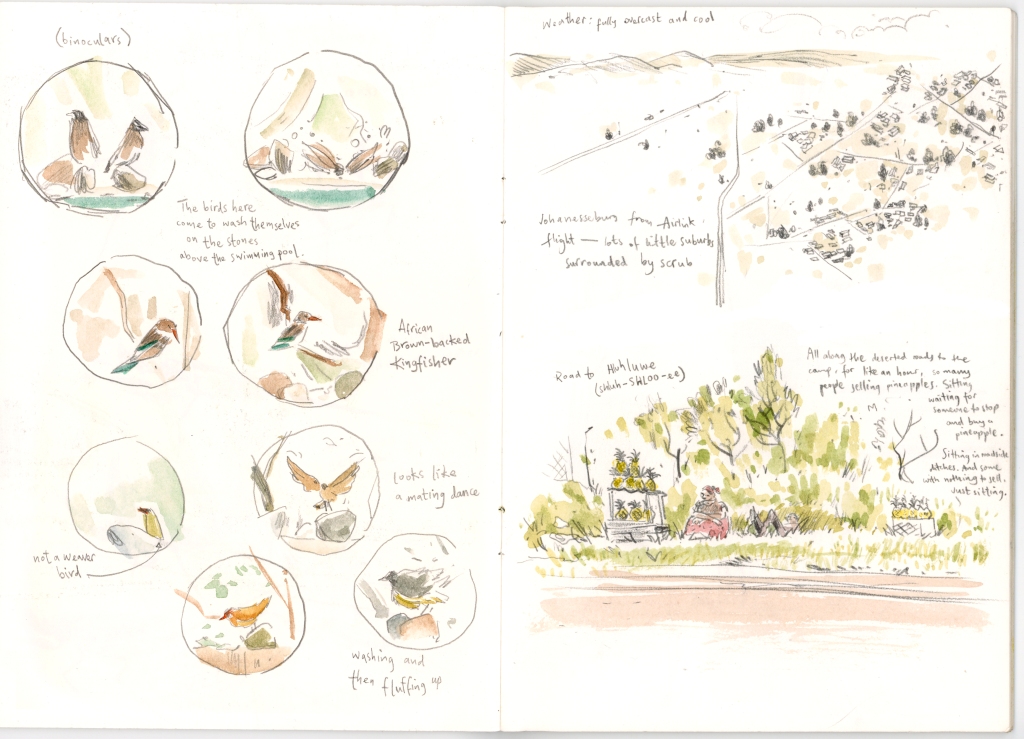

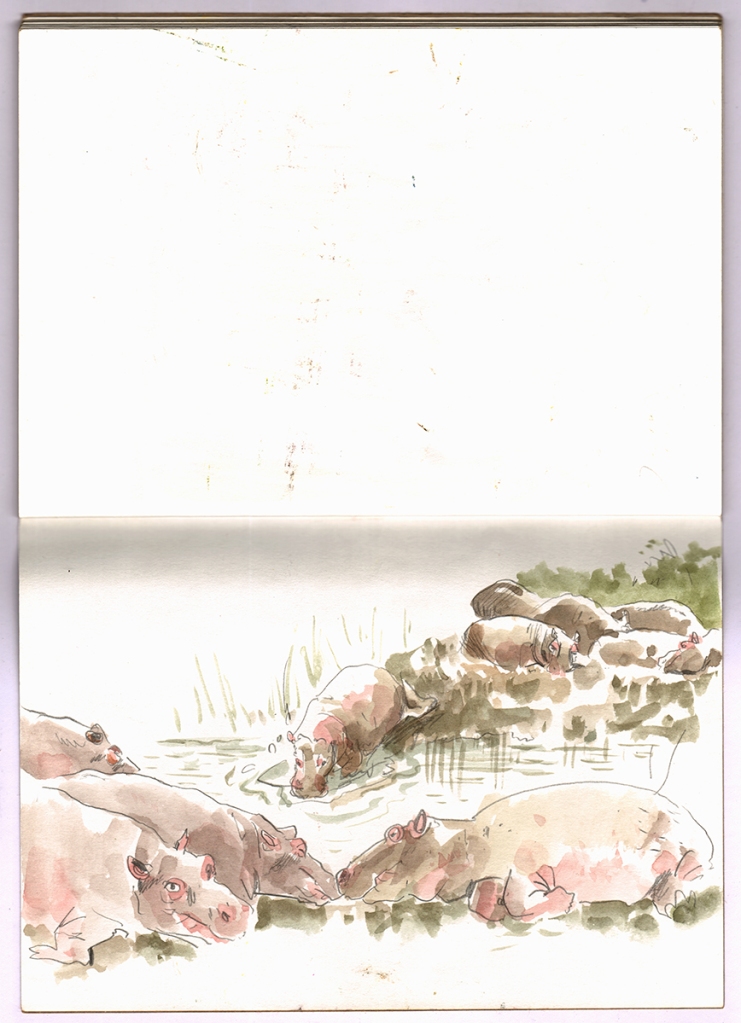

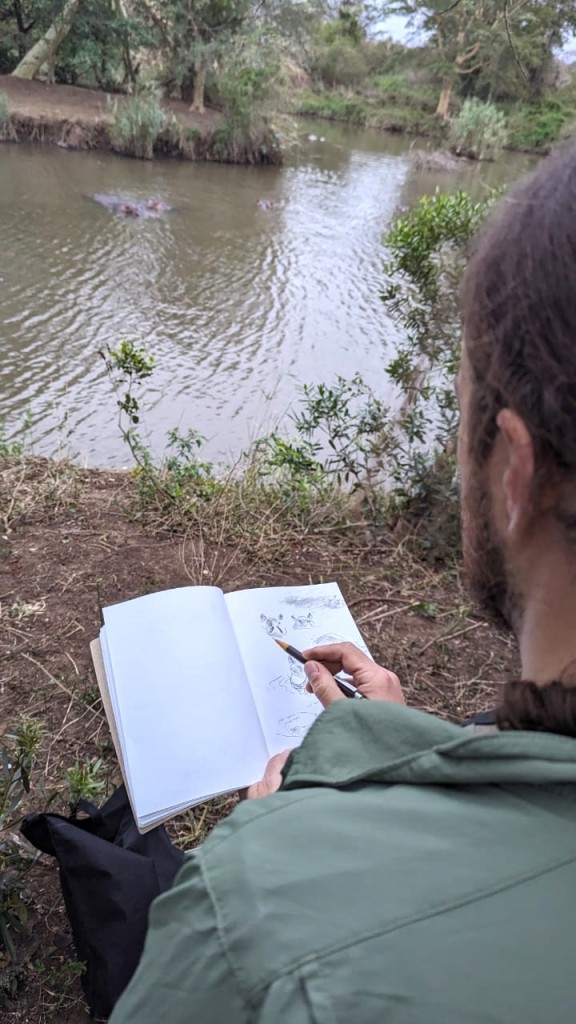

Though I had begun the trip hidden behind my sketchbook, my immersion in the place became such that by the first weekend I neglected to draw for a couple of days, stunned and simply taking it all in and enjoying getting to know everyone.

But then, remembering the intended purpose of the trip, I returned to my drawing and note-taking with a renewed vision: that I could use the sketchbook to communicate my emotional and totally subjective experience of the beauty and importance of the threatened natural world, as well as the people working to protect it.

Compared to the tireless work of those who wake up every day and go out there on this mission, I do have to wonder what small part my abilities can contribute to the cause of conservation. But when I experienced the response people had to my drawings, I began to understand the importance of communicating experience, and that there can be something specially significant about a drawing or a very personal piece of writing.

I was even more fortunate to be travelling with fellow book creators as part of CBCC, and had the companionship of sketching alongside wonderful artists like Eric, Brian, and Jessica whose talent and experience and generosity of spirit were both humbling and an inspiration.

‘If I went in to this with a hamfisted idea of what conservation meant’, I thought, ‘Maybe other people have the same unclear or stereotypical vision of all this, and maybe I can share some of my dawning understanding with them.’

Can a drawing capture something that a photograph or a video can’t? Again and again people told me, yes, it can. Drawing opened up conversations with rangers, landowners, vets, locals, and fellow tourists from all over, and what wonderful conversations they were: driven by their love and awe for what was in front of us, a love and awe that they helped me to discover too.

I guess there’s a being there in drawing that people respond to. Someone asked me, ‘Why not take a photograph and draw it later?’ But that would only be drawing animals. And going into the experience, I had worried that drawing animals was all it would be.

But being there, and being a part of it, mattered. From people’s kind and open responses to what I was doing, I learned that by being there I could do much more than simply draw animals: I learned that I might be able to articulate something of how it feels to be there, in the trees where an elephant has fallen, to feel her heated breath, the pulse in her ears, the texture of her skin. And the mood, the tension, the atmosphere. And the determination and care of the people who do this work.

I see art as a way of communicating things that can’t be described in the ordinary ways. There are things we can feel and see that defy simple description, and we saw these things every day. I like to think that this is why poetry exists, to give us the means to articulate feelings that can’t be articulated.

I just hope that a little something of my appreciation for the dignity and vulnerability of these animals and these people, and these places, can come across in my drawings enough to inspire others to feel something of the understanding that dawned at these moments of intensity.

It would be tempting to tell everyone to go buy a ticket right now and hotfoot it to KwaZulu-Natal for two weeks with Wild Tomorrow (and if you’re an artist, a photographer, a poet, or simply a dreamer, then you should consider it if you can), but I also took away a broader message.

We go through many things in life, and each of us lives a different life. There are places you will go that I never will. You may live most of your life in a faraway city I yearn to visit but never will, with your own dreams and fears, ecstacies and heartbreak. We can each only live one life. But by keeping our eyes and our hearts open, and by making art in any way we can, I hope we can let each other in to our own subjective experiences, and see a little bit through each other’s eyes, and live a little bit of each other’s lives, and capture some essence of the fleeting moments in time that make us who we are, and finally understand one another.

Although I went in as a clueless bystander, unconvinced that I had the spirit to rise to the experience, I found myself deeply moved by the things that the people at Wild Tomorrow worked tirelessly to make us a part of and by the glimpses that I had of the lives that go on there. My simple little sketchbook was merely a tool that helped to make this connection happen.

I still need to figure out how to develop all this into something that can contribute to Wild Tomorrow and the wider cause of public communication of conservation issues which is the mission of CBCC. But just going, and being there, was overpoweringly positive, and, I hope, the first step in something very good, and one of the most enriching and fortunate experiences of my life as an artist.

(Photos courtesy of Greg Neri and John Rocco.)

Filed under: drawing, drawing theory, sketchbook, south africa | Tags: art, drawing, illustration, sketch, sketchbook, travel, travel diary, travel drawing, travel journal, travel sketch, travelogue

I’m not very good at talking.

The idea of going on a trip where I would be with a large group of mostly strangers all day long for two weeks fills me with anxiety. This October I did just that, travelling to KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa with CBCC (Children’s Book Creators for Conservation) to work with Wild Tomorrow.

I have much to say about the work of the conservation groups we met and the value of art and books and public communication in helping to tackle the considerable issues facing our natural world, but my initial surge of feeling and thought regards the people I got to know in South Africa and the power of drawing in real life.

I didn’t prepare adequately for the trip.

I had a fairly profound anxiety response to the upcoming trip and the emotional and social demands it would make. My response was to shut out these demands and refuse to think about them. As it approached, I seriously considered cancelling the trip several times.

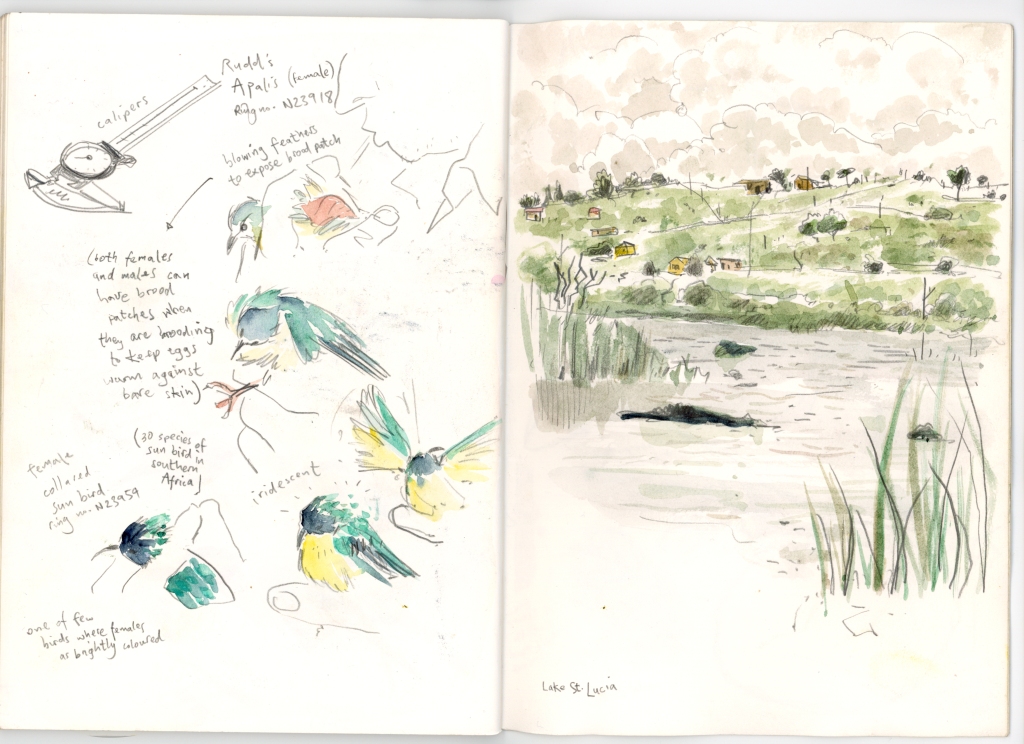

I decided that to cope I would use my sketchbook as a shield, a place to hide my eyes, something to busy my hands. Maybe I could hide myself behind that sketchbook for two weeks.

But then something else happened.

The sketchbook, rather than becoming a wall, became a window. Rather than a way of avoiding communication, it became a way of communicating.

To my surprise and profound joy, my travelling companions, rather than seeing my drawing and note-taking as something antisocial, saw it as a direct communication of what I was seeing with my own eyes, and what I was feeling and thinking.

It was as if by drawing, I was opening a dialogue with people.

Throughout the trip, not just artists, but all kinds of people approached me by using my sketching as a way in. How many people feel comfortable complimenting a complete stranger, ordinarily? But when you draw, people do. They smile and they like you. They laugh if you’ve captured a drawing of someone they know. They talk about their own creative projects, or their children. It’s like they see something of your naked soul, and feel they can trust you.

My kind and generous companions in CBCC told me with a frankness I’m not used to that my drawings enriched their own experience of the journey. Many of them are artists themselves, and of vastly greater talent and experience than me, so to have felt that I could contribute to their experience in my small way is nothing short of a blessing.

Drawing my experience of things allowed me to engage with what was happening in a way I couldn’t have without drawing. And not only that, it allowed me to share my experience of things with others.

And people understood.

I underestimated how open and authentic people can be when you reach out. I didn’t really know how to reach out, but I discovered that you can do it with a drawing as much as with speech.

As the trip went on I found myself regretful only that I hadn’t done more in advance to get to know the people and the places I would be going to, and to contribute to the good-hearted work that Wild Tomorrow and CBCC are doing.

I hope that this is just the beginning for CBCC led by Hayley and John Rocco, and for my relationship with them and all the other wonderful people involved.

I started listing everyone to thank, but there are so many that I am bound to miss someone out. Just know that if I met you in the past two weeks: thank you. The kindness and spirit and generosity of you all has been one of the great privileges of my life to experience.

Please consider donating to Wild Tomorrow at: wildtomorrow.org/cbccdonate

Filed under: drawing, drawing theory, illustration, sketchbook | Tags: art, camping, drawing, how to draw, illustration, sketch, sketch daily, sketchbook, sketchbook inspiration, sketchbooks, sketches, walking

When I go on a camping trip I always take a small sketchbook.

And at first it seems like I’m going to be too exhausted from walking with a heavy backpack and sleeping on the ground to actually draw anything.

But every time there’s this point where I see one thing that calls out to be drawn, and the floodgates open.

Usually during the latter part of the trip I’ll be drawing non-stop, doing several sketches in a row in one location.

It’s an abbreviated version of what it’s like to work on art more generally, especially novel-length books: nothing happens for a long time, and then suddenly it starts happening and comes in such a torrent that you can’t remember why there was so much dithering and chin-stroking before.

These are from the North coast of Norfolk.

Filed under: amy & kay, comic artists, comics, comics theory, drawing, drawing theory, faith in strangers, graphic novels, my comics | Tags: art, art theory, cartoons, comic strip, comics, drawing, graphic novel, graphic novels, how to draw, illustration, making comics, wab sabi, writing

“Nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.”

Comics has a spontaneity problem.

Chris ware said that, unlike writing prose or playing music, it isn’t really possible to get into a creative flow when making comics, that the technical demands are too complex and the rate of creation too slow.

The classic way of drawing comics is pretty convoluted. Script, thumbnails, roughs, underdrawing, inking. In fact, almost all comics were traditionally made by teams of three, four, five, or more people all doing their own separate bit to cobble it together.

But what really matters? I care about dialogue and relationships between characters more than anything. Do I care about comics having stunningly beautiful artwork? Well, yes, to an extent. But most of the time, artwork that is too involved, too complex and eye-catching, actually distracts the reader from the story. In a comic, the drawings should be in the service of the story, not in the service of themselves. So when we agonise over every panel, trying to make it a work of art in its own right, we may actually be doing more harm than good.

In trying to find a way to make art without being neurotic about it, I’m making myself work in ways that force me to embrace imperfection. The way I see it, however hard one tries, the result is bound to contain imperfections.

In fact, the acheivement of ‘perfection’ in art is asymptotic, i.e. you can approach it, but never reach it, and as you get closer, exponentially more energy is required to make further progress.

Or in other words: the first 90% requires 10% of the work, and the last 10% of the work requires 90% of the effort.

So maybe it’s better to embrace imperfections rather than engaging in the desperate struggle to overcome them all.

I’m starting to realise that the attempt to iron out all kinks in a piece of writing or drawing is mostly a barrier to progress.

Wabi-sabi is a concept originating from Japan that embraces the transience and necessary incompleteness of anything humans create. Starting from this idea leads one to principles of simplicity and finding natural approaches to creation.

I’m having a go at drawing comics with the most natural approach that I possibly can. Two projects I’m currently working on, my graphic novel Amy & Kay and a daily comic strip Faith in Strangers, are both drawn in pencil without much planning or any underdrawing, and with the intent to embrace imperfection as far as I can bring myself to do so.

When things go right, drawing this way looks more spontaneous and interesting than any laboured-over drawing. When it goes wrong, it’s imperfect, but somehow hangs together with everything else, and balances with the parts that are more successful or complete.

Make the unfinished and imperfect nature of the work part of its essence, like a painting with areas of blank canvas, or a song that cuts off in the middle of the climactic moment.

Filed under: drawing, drawing theory, illustration, sketchbook | Tags: art, books, drawing, illustration, life drawing, sketch

Whenever there’s an event featuring a graphic artist of any kind and they end up fielding questions from the public, there are certain questions that always get asked, and probably the one you hear the most is:

“What would be your advice for someone who wants to be an illustrator?”

This question is usually posed by a starry-eyed youngster, perhaps even a small child, just dying to know that one, closely-guarded secret that will cause them to become a successful graphic artist.

Of course there are no secrets. Or if there are, I don’t know them. But there is a specific answer most people give to this question, and it’s a very good answer.

I was recently lucky enough to attend the Harry Potter Book Night to hear illustrators Jim Kay and Chris Riddell in a panel discussion about their work, and Riddell, inbetween his usual bouts of very fast and impressive live drawing fun, was asked this classic question, and gave the classic answer.

The answer to this question is always, “Keep a sketchbook.”

That’s it. Usually followed by the suggestion to keep it with you at all times and draw anything at all, as much as possible.

And if you want to become good at drawing and figure out how to world looks and how to capture as much as possible with lines on a page, then there really is no better advice. The more you draw, the easier it becomes. But as simple and effective as this advice is, it can be very difficult to follow.

A little while ago I went through an intense period of sketchbook drawing for a few months. I’d filled two thick books and was in to my third before it fizzled out again. This is normal for me. I go through heavy periods of sketching, and then I leave it for a while. Basically it’s because doing it properly is so time-consuming.

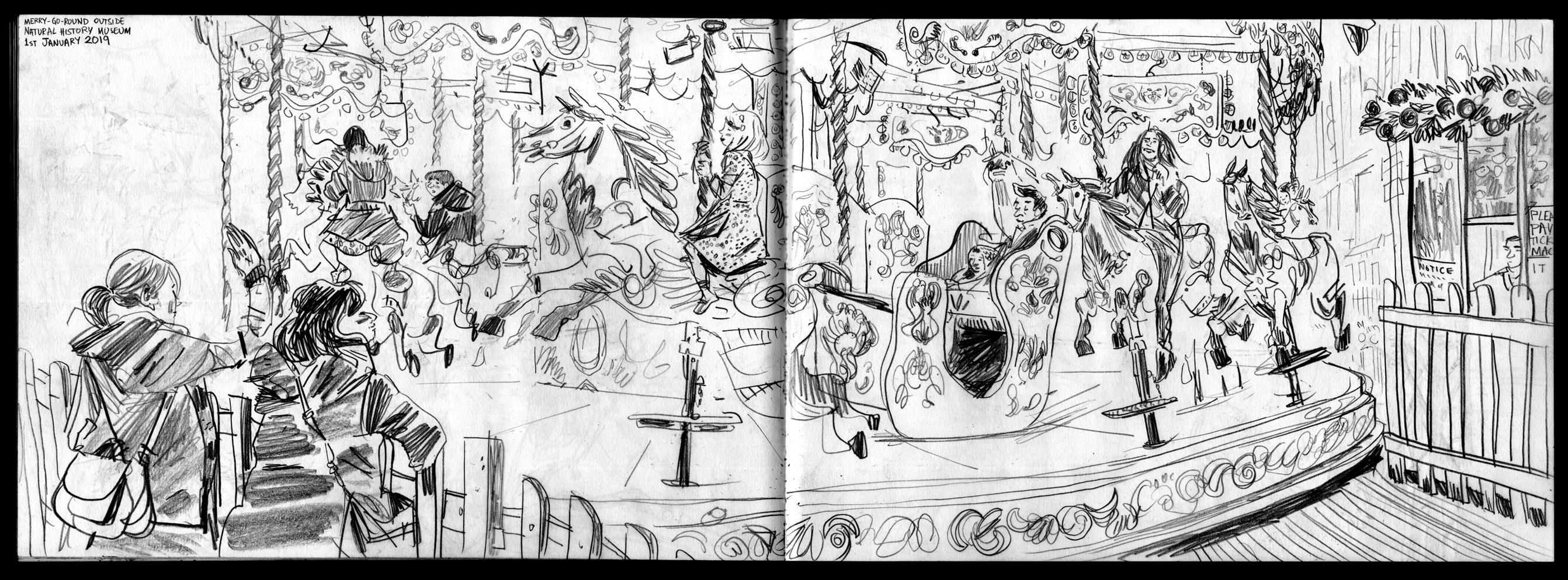

Doing one-minute doodles of people on the bus is fine, but if you want to get stuck in and seek out and draw big, full, unique scenes from life, you have to commit to sitting there for a good long time. I tend to spend around an hour on drawings like the ones you see here. So when I do it, I have to commit to it, and go out and spend entire days working on this stuff. It takes a lot of energy.

My point being, I suppose, that if you take the perennial advice of keeping a sketchbook (and we all should), don’t beat yourself up if you don’t finish off a thick book of fully-detailed, unique and exciting drawings every month. This stuff is hard, it takes time and patience, and the only way I’ve found to do it properly is to take a good, long look at the world in front of me and settle down into it as patiently and openly as possible.

Filed under: drawing, drawing theory, illustrations, sketchbook | Tags: art, drawing, illustration, life drawing

Recently, I took a small sketchbook and a pencil to Devon.

In drawing landscapes and scenes from life I’ve been thinking in terms of ways of handling particular visual elements, i.e. how do you make sense of the world in front of you and actually have your drawing appear immediately to the eye as being the view you were looking at?

You’d think it would be simple. If you just draw what’s in front of you accurately then you’ll end up with a good facsimile of what you were looking at, surely. This is often true with highly skilled impressionistic painters, dabbing carefully chosen colours onto the canvas, and literally getting down what their eyes see until gradually it builds up into a coherent image. But for many types of drawing and painting simply getting down exactly what you see is not enough. More than that: it doesn’t work.

Say you’re drawing with nothing but a grey pencil on white paper. You sit down to draw a landscape. You see an area of bright white sand next to an area of dark rock in shadow. This doesn’t present any real problems. Leave the area of sand mostly white on your page, and make the rocks very dark. But then you look up, and above the sand is the sky. The sky is neither light nor dark: it’s bright. And it’s very distinct from both the sand and the rocks. You’ve already used a light area and a dark area, so do you put the sky down as a mid-tone? That doesn’t really work, it’s too bright. It should be white on the page. But the sand is white on the page, already. So you end up drawing a dark line of pencil to show the line where the sky and the sand meet, even though that line isn’t there in real life. You might even see someone’s lime-green windbreaker or hot-pink parasol against the sand and the sky, and those will have a different quality again.

These are the things I’m trying to find ways to handle when sketching recently. A drawing is not the same thing as real life, and I’m trying to find methods to interpret things so that they communicate on the page. I’m trying to define shapes of certain qualities, colours and textures so that they are immediately distinct. It’s all too easy for a pencil sketch of a scene to devolve into a mess of lines, where everything has the same quality and nothing stands out from anything else, because I’ll have tried to draw everything in the same way, just marking down what I see. But by using defined areas of pattern and tone, and differentiating objects and areas by using varying qualities of line, and by treating identifiable objects as separate and clearly-defined against what’s behind them, I’ve been able to get a lot more clarity than I usually do out of some very simple pencil sketches.

Filed under: drawing, drawing theory, illustrations, sketchbook | Tags: art, drawing, illustration, life drawing, sketch

Can you learn new things unconsciously?

Skills like riding a bicycle aren’t really skills until you can perform them subconsciously. No-one can ride a bike well if they have to think consciously about the movement of each arm and each leg, and consciously keep balance and so on. You’re not really riding until you’re doing it without thinking about it.

I’ve been doing a lot of life drawing recently, and I’ve started to notice a distinct pattern in the quality of my drawing.

Here’s how it goes: sometimes I tell myself to buckle down and really concentrate on executing a careful, tightly-observed drawing, taking note of as much as possible, and relating as many areas to as many other areas as I can. What usually happens when I do this is that I do some interesting bits of drawing; some novel local observations, but I do not do a good drawing, which is to say, a good, whole drawing; the parts do not hang together into something harmonious.

Usually the drawings I produce when I focus very consciously in this way make me frustrated because they end up being ugly to look at and I can see how unsuccessful they are at capturing the person I’m drawing, so after a few of these perceived failures I tend to stop focusing and relax into drawing very quickly; more quickly than I can think; letting my hand take over from my brain; drawing subconsciously. Almost invariably when I do this, I end up producing quite nice, harmonious drawings and it gives me a lot of pleasure to do. Additionally, it takes little energy; indeed, I often end up invigorated after drawing this way; I feel full of energy, as though I could draw all night.

So what’s the problem? Just draw subconsciously, right? By delegating responsibility to my hand, my subconscious understanding of drawing takes over and makes things easy. But I started to think about this, and it occurred to me to ask: how did I gain that subconscious ability to draw? Because I didn’t always have it. Surely it must have been through the struggle of drawing consciously, and so paying attention to things very closely and actively and, through long, difficult work, committing the knowledge that I picked up consciously to my subconscious.

It makes me wonder: when I draw in this nice, very enjoyable, subconscious way, am I learning anything? Or do I only learn new things and improve my drawing by doing the difficult thing of being fully-aware and drawing consciously? And isn’t life-drawing, when you’re trying to learn rather than create your best, illustrative work, the time to do that?